Whether you’re a beginning Trumpet player or a seasoned professional you could be anywhere on the spectrum from sanitizing your Trumpet mouthpiece every day to never really bothering with it. If there’s a goal to this post (nope, that’s not a sports pun) it would be to encourage you to be better than I am at keeping your mouthpiece clean.

Clean your trumpet mouthpiece every day by rinsing it with clean chlorinated water. Scrub the inside with a mouthpiece brush and a sanitizing solution at least twice a week to decrease the amount of bacteria on the surfaces. A clean mouthpiece will also sound and play better than a dirty mouthpiece.

I’ll do a YouTube video to demonstrate the difference a clean mouthpiece can make to your playing. This post is where you’ll see the real story about the potentially harmful bacteria that you might be providing with a nice place to reproduce.

PLEASE NOTE: This post is the creation of a Trumpet player and retired Band teacher. I’m not a medical doctor and I’m not a scientist – just me, with a little help from my friends (old guy reference).

Cleaning your trumpet mouthpiece

If you don’t like to read a whole lot then scroll through this article, look at some of the photos and decide not to get sick from your Trumpet. Look at the pretty pictures and find the place where I talk about Sterisol.

Why you should clean your mouthpiece

This post is the result of my symphony orchestra playing colliding with my “day job”. I got really busy this Spring because someone roped me into teaching high school band every day for a couple of months. At some point in the fog that job created in my otherwise calm retired life, I played a series of concerts that included Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony (#3 if you’re counting).

As usual I was on second Trumpet and my part at one point had a whole lot of low G’s. It was written for Trumpet in C at that point, so that would have been an A below the staff on a regular Bb Trumpet. I noticed that on the loud ones I just wasn’t playing as clearly as I would have liked. I was switching back and forth between my old Bach C Trumpet and a Yamaha C Trumpet that a friend was thinking of selling and I couldn’t get either one to respond cleanly.

Why am I telling you this? Well, I’m embarrassed to say that the problem was in my mouthpiece – literally. I’m not sure what made me look in there but when I did, I didn’t like what I saw. A clean mouthpiece – and I’m talking about the inside of it – should be smooth and shiny. Mine didn’t look gross but it didn’t have that perfect glossy sheen either – time to wash it out.

If you’ve seen my Trumpet cleaning video then you know that I use a white laundry tub to clean my trumpets. Against that white backdrop I could see a super-thin slimy skiff of sludge float out behind the mouthpiece brush. Naturally, I took the mouthpiece straight back to my Trumpet, put it in and hammered away at a bunch of low G’s. Clean, clear, centred lovely notes just fell out effortlessly. Keep your mouthpiece clean if you want to always sound your best. As glad as I was to have solved that little problem I was left feeling pretty stupid for having let things get that bad. Life had got busy, I didn’t have time to clean my mouthpiece, it looked clean, my dog at my homework – excuses.

Please learn from my mistake – clean your mouthpiece regularly so that you sound better BUT that’s not even the best reason. The best reason to clean your Trumpet mouthpiece regularly is so that you don’t make yourself sick. After the episode above I asked a Science teacher in the high school I was working at if he could help me figure out just how disgusting my mouthpiece was on an average day. (This was after I had cleaned it as described above.) It took us a week or so to find a day when we could make that happen and I decided not to clean my mouthpiece again until that event. A week or two is not a long time for most players to leave a mouthpiece between cleanings. Plenty of players only really clean them thoroughly when they wash out the whole instrument. I’ve openly teased a certain trombone player for fastidiously washing his mouthpiece every single day before he plays a note. I’m sorry Gordon – I hereby retract every smirk, eye-roll, head-shake and uncharitable thought on this subject. You were and still are right. All of the results below came from a mouthpiece that I would have considered “relatively clean” before we started. If it fell in my soup I would have kept eating.

The science behind cleaning your mouthpiece regularly

The Science teacher, my friend Geoff, had prepped a dozen Petri dishes by “cooking” them in an autoclave so that they were absolutely sterile (super-clean). Without giving you all of the gory details we took swabs from my mouthpiece before and after a few levels of cleaning and then, just for fun, a couple of other spots on my daily driver Bb Trumpet. We doubled-up on the first spots to make sure there were results that we could see, so I’ll be leaving out a couple of samples. These swabs were smeared on some Agar, which is a kind of jelly that encourages bacteria to grow and then we put the dishes of this yumminess into a little oven that kept itself at just around body temperature for the next few days to see what might grow. There were no Haz-Mat suits involved but we tried to keep everything clean so what you see here is pretty reliable. Geoff used to pay his bills working in a lab so he knew how to do all of this properly – and safely.

High Schools are great places to work. When Geoff and I were trying like a pair of Gumbies to take pictures of these samples we stumbled into the school’s yearbook sponsor and photographer extraordinaire – Jonathan. He not only recognized how poorly prepared we were to take decent photos, but as soon as he gagged down his lunch he came by and took these photos. I think he was glad that he’d already eaten.

Geoff told me that in all likelihood we would come across Strep and Staph (Streptococcus and Staphylococcus) bacteria because of where we got the samples and because we incubated them at body temperature. These bacteria are in and around us, so finding them would be no surprise. The question was more to do with how plentiful they’d be on my mouthpiece and nearby. Too much of either of those bugs can make you sick. Geoff did think that the metals in and on my mouthpiece might offer some protection from mass bacterial growth, and that our results might be inconclusive.

There is another offender out there that can be even more serious; something called hypersensitivity pneumonitis. That’s not a bug, it’s a rare condition that results from a few people’s reactions to a plentiful bug, mold or fungus and it can kill. Yup. DON”T FREAK OUT. Just keep your mouthpiece (and your trumpet) clean. This HP thing is exceedingly rare. Anything you have around your mouth or nose is something you want to keep clean. A few bacteria here and there probably pose no threat, but you don’t want so many that they are out of control. Mold and fungi likewise. Cleaning your mouthpiece is about making life difficult for these micro-organisms. Let your immune system take care of the few that get past your defences (maybe from that piece of pizza you found leftover from yesterday – on the table).

Ok – the results:

Samples 1&2

from the cup of the mouthpiece, recently used – not washed for several days:

Sample #1 shows such a solid cloud of bacteria that even at the fourth level of separation there is just too much to evaluate. It is foul.

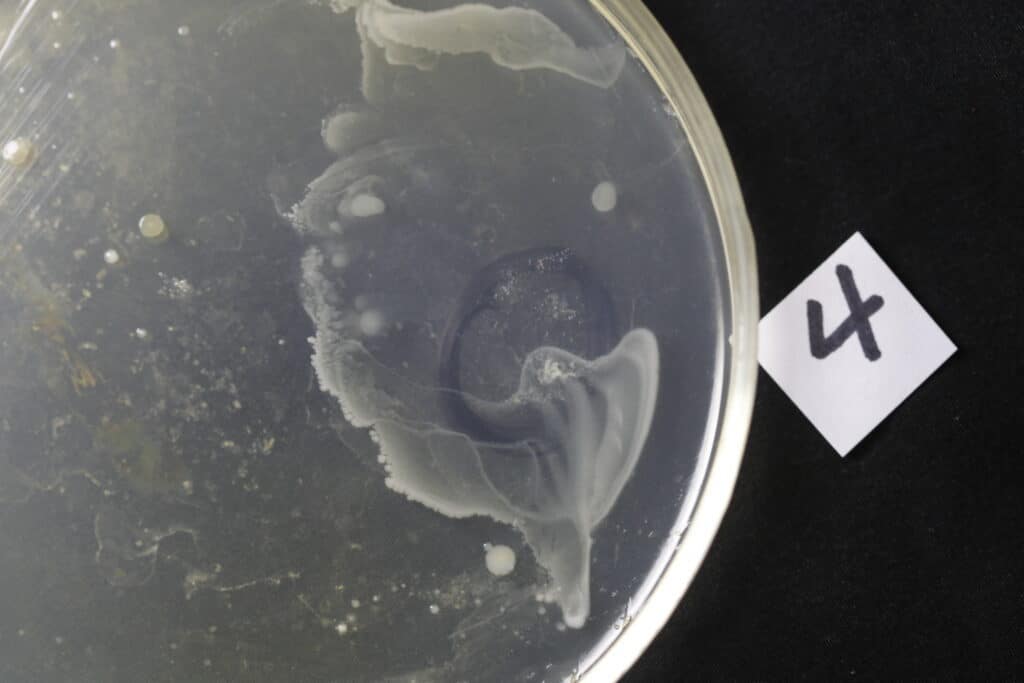

Samples 3&4

from inside the backbore of the mouthpiece, recently used – not washed for several days:

Sample #4 shows multiple colonies (the little roundish blobs) in the swishes at the top left, but mostly just the same overwhelming that the Sample #1 showed. Yuck.

Sample 5

from the cup of the mouthpiece freshly rinsed with chlorinated tap water:

Sample #5 shows some distinct large colonies of what I think is Strep (“orders of magnitude fewer colonies”) and an underlying fog of out-of-control Staph.

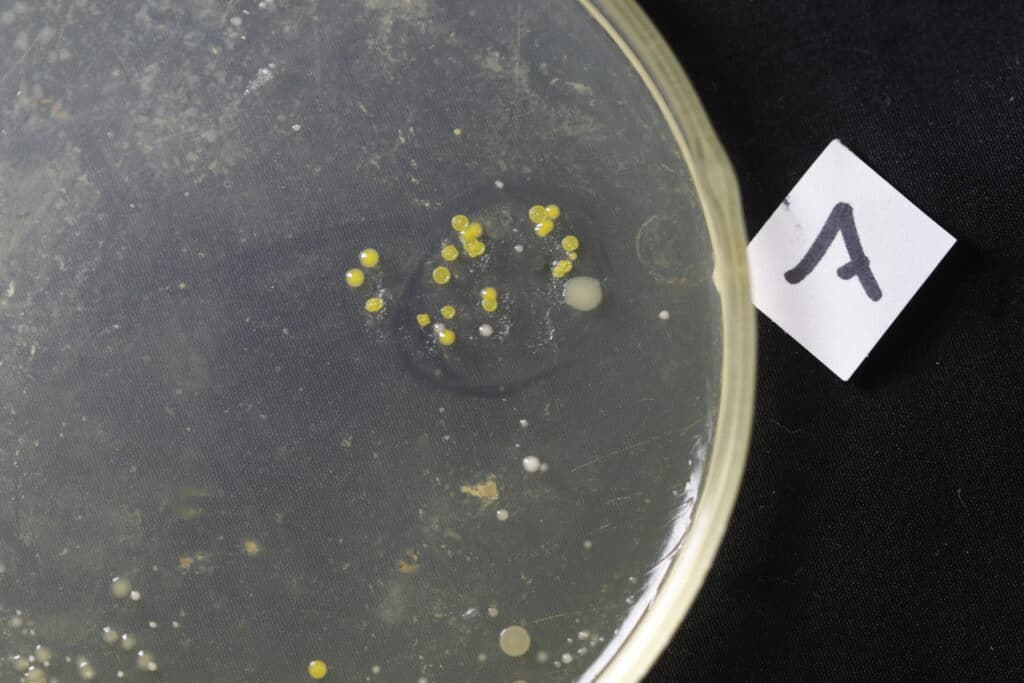

Sample 6

from inside the backbore of the mouthpiece freshly rinsed with chlorinated tap water:

Sample #6 shows thousands of visible little yellow colonies and a handful of “juicy” big white ones.

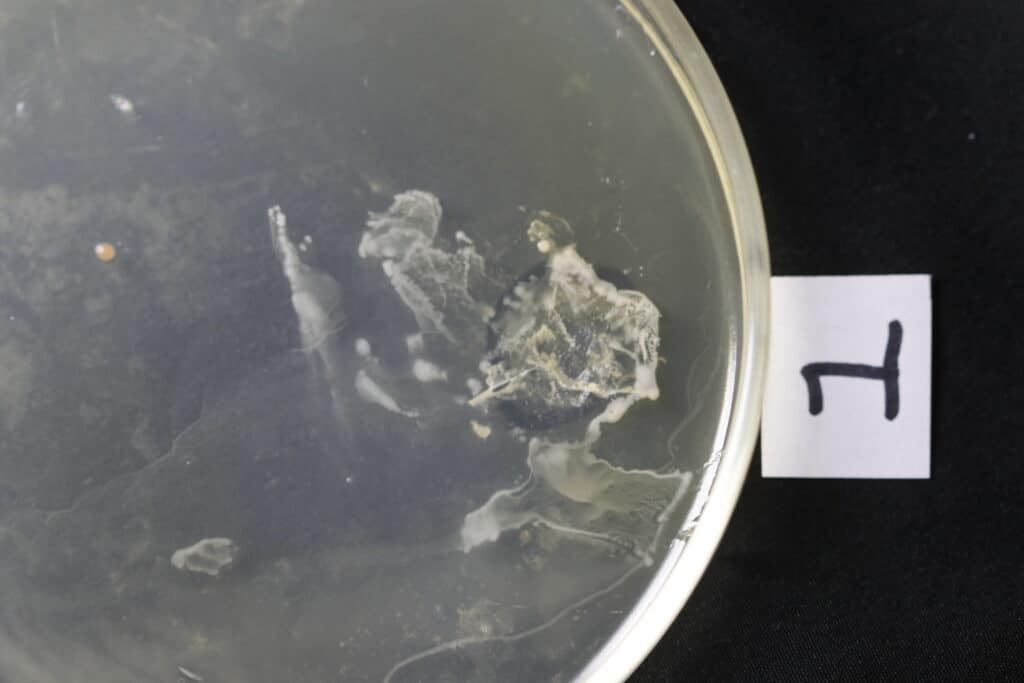

Sample 7

from the cup, freshly rinsed and brushed with chlorinated tap water:

Sample #7 shows lots of individual colonies which are “quite healthy” because they aren’t “living in the sewage of others” (I’m quoting Geoff, the Science guy).

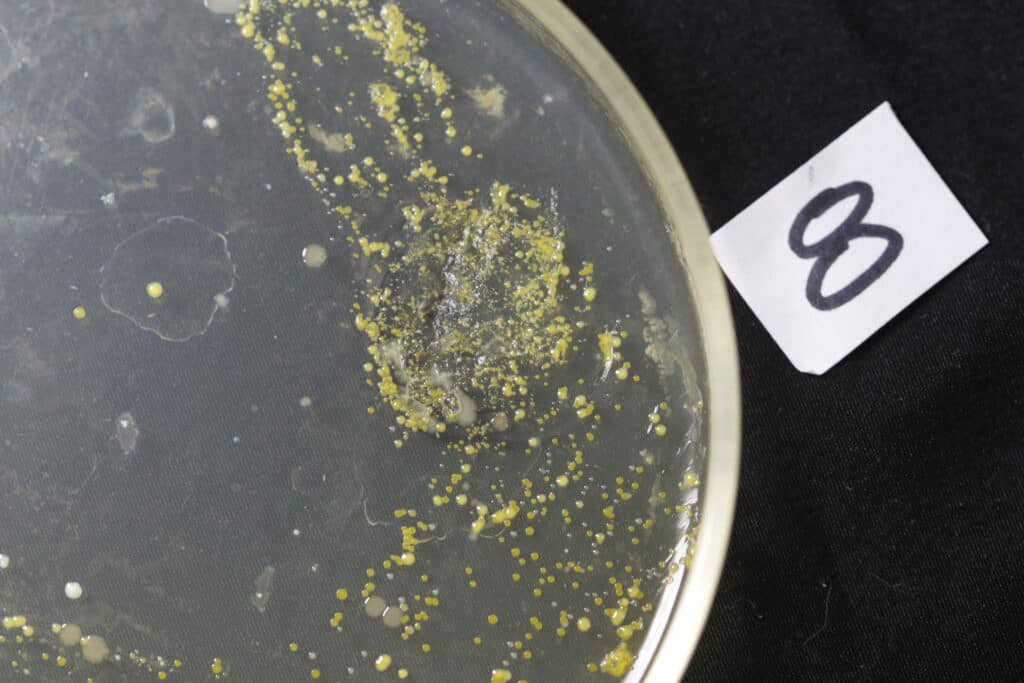

Sample 8

from inside the backbore, freshly rinsed and brushed with chlorinated tap water:

Sample #8 is much the same as Sample #7, just with more colonies. That makes sense.

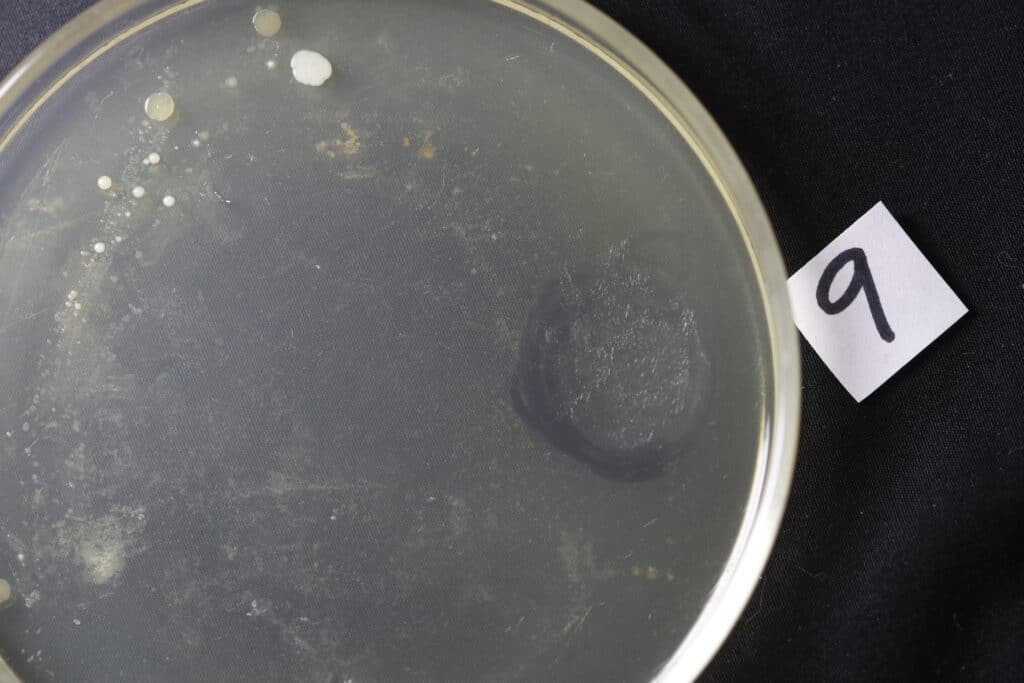

Sample 9

from the cup, freshly rinsed and brushed with Sterisol*, then water:

Sample #9 shows the results of our chemical attack (Sterisol). The yellow is almost gone and the white is struggling. (I’m sure that if I had followed the instructions the Sterisol would have killed off the survivors.

Sample 10

from the backbore, freshly rinsed and brushed with Sterisol*, then water:

In Sample #10 both strains are doing better, but still the yellow is clearly struggling. (Having now swabbed this backbore 3 times, rinsed it, brushed it and sanitized it this might be the image that changes my bad habits.

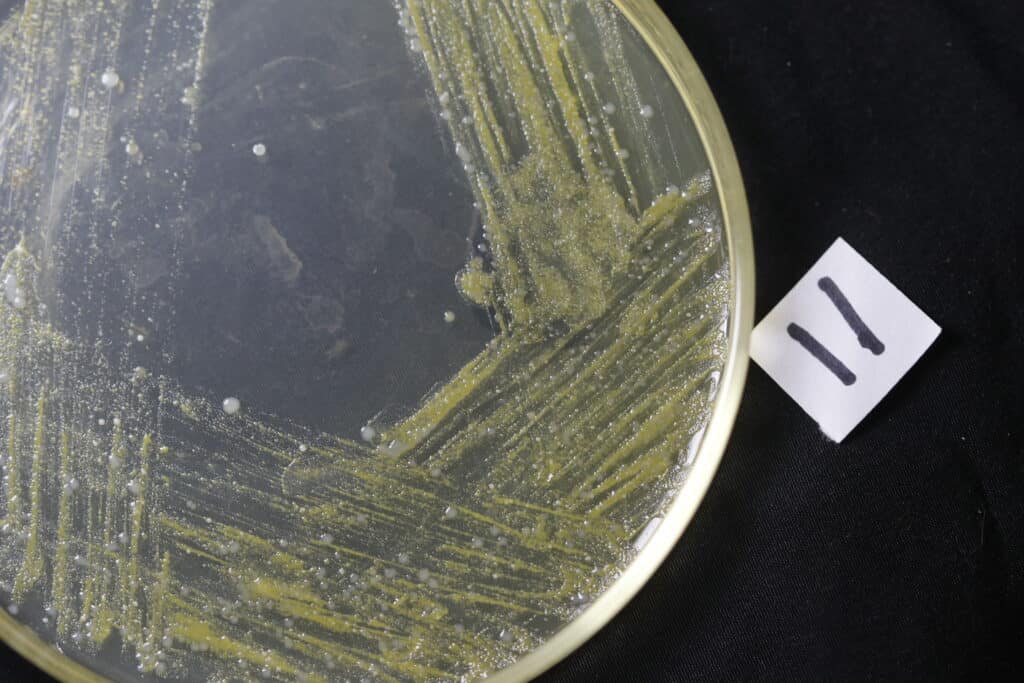

Sample 11

from inside the Trumpet leadpipe just beyond the mouthpiece receiver:

Sample #11 shows “no separation” which I think is science-speak for “crawling with bacteria”.

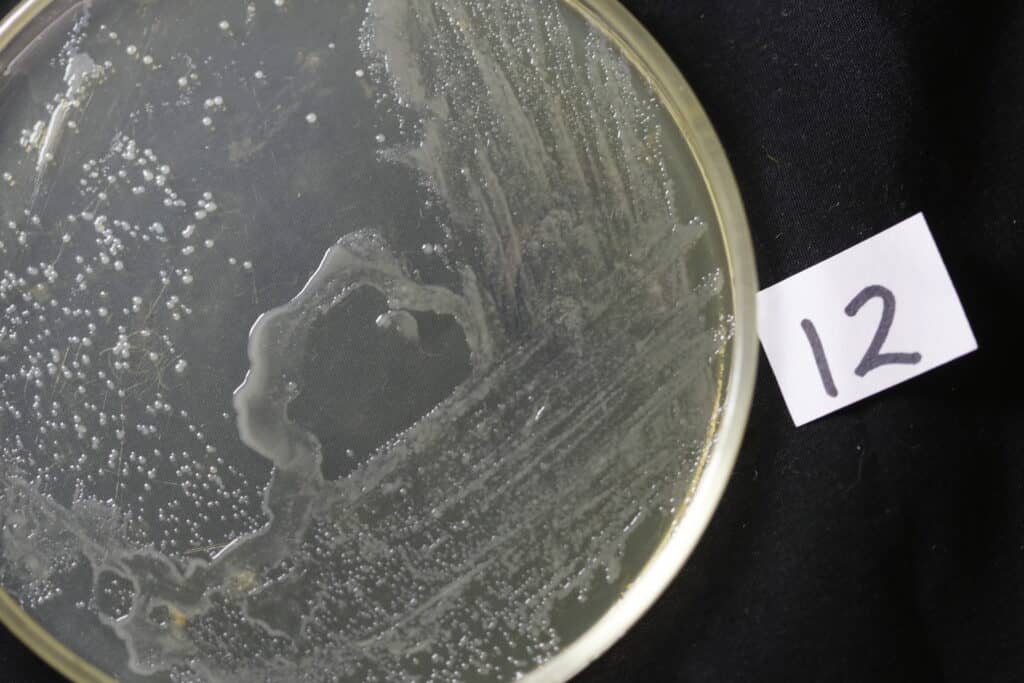

Sample 12

from the “water key” (aka spit valve):

Sample #12 shows a sea of the white bacteria that never really thins down. Maybe there’s a reason that Trumpet players call it a spit valve, and manufacturers call it a very clean sounding “water key”.

Some Thoughts …

A word about the photos and their descriptions. When your goal is to see how effectively bacteria is reproducing you try to dilute it a number of times. The samples here have all been treated the same way. Geoff dabbed the swab in the Sharpie circle then swished it back and forth, then rotated the dished and swished again, then rotated etc. etc. Its easiest to see in Sample #11. Each set of parallel swishes is a dilution of the previous set. As a sample is further diluted you should be able to see individual colonies of bacteria along the swishes. Geoff calls it “separation” when you can see the colonies. I think the staph is mostly yellow and the strep is mostly white.

- I used the Sterisol the way I always have, and the way I’ve always seen it used. I sprayed it on, scrubbed a little with a mouthpiece brush and rinsed the results off. That is NOT what the instructions say to do. Almost every product that kills bacteria tells you to leave their product on the item being cleaned for a period of some minutes. I think Sterisol says 2 minutes. That’s how they get the best results. If you want to use their product effectively – or any other – do what the instructions tell you to do. Sample #9 shows what that product can do even when someone like me doesn’t take the time to read or follow the instructions printed clearly on the container. Hmmm.

Finally …

I am old, but not too old to learn from my mistakes. I’ve brought the Sterisol bottle in from my repair kit to where I practise and will use it regularly. I’ll even follow the instructions occasionally.

I’m not afraid of a few bacteria living on the things I touch but I’d really prefer not to expose myself to them in concentrations so large that they are choking in their own excrement and dying for a host.

There are probably other forms of chemical death that you could use to kill bacteria on your mouthpiece. Sterisol is made for that purpose and is safe when rinsed off – AS PER INSTRUCTIONS!!!

And one more thing …

The virus behind the COVID-19 pandemic is protected by an oily outer layer which is easily defeated with almost any everyday soap. That’s why public health people have been going on for years about washing your hands! Soap kills COVID so using a little on your mouthpiece from time to time might be a good idea. Besides, this whole post got bogged down in bacteria and we never really talked about just getting the sticky goo, chunks and crud off that mouthpiece. Soap is good.

P.S.

Billions of bacteria were harmed in the preparation of this post. The Petri dishes used were put straight back into the autoclave and my new little friends were vaporized out of existence. Many thanks to Geoff for making this happen and to Jonathan for the photos.

P.P.S.

Don’t try this at home!