It is the best of skills, it is the worst of skills. If the thought of trumpet transposition drives you to the winter of despair fear not – the spring of hope blah blah blah.

That reminds me … it’s Spring here and the first Trumpet shoots are popping up through the snow!

Introduction to Trumpet Transposition

We have to start with the easiest and most important transposition for all Trumpet players and the only one most players will ever need – down an octave.

By the time you hit your second year in school band some of you will need this transposition. Some composers, some arrangers and definitely some band teachers don’t seem to understand just how difficult it can be for beginning Trumpet players to play higher notes. The ability to look at a part and play the notes down an octave is a crucial survival strategy that virtually all Trumpet players use. It might be the first good reason to learn the note names.

When you are faced with a note that is higher than you can comfortably play you should force yourself to play it down an octave rather than forcing yourself to squeak it out. Tax your brain, not your chops. If you start this early in your career you will only have a few notes to think about – do it. You’ll be glad when your conductor drags you through something high and long for the umpteenth time.

Transposition for Trumpet Players

Some of us stumble into transposition accidentally and others are hit with it in the face. Eventually everyone with a trumpet will find that they have to play what they know to be wrong notes so that they sound like right notes. That’s transposition in a nutshell. Given that pretty much everyone starts on a Bb Trumpet (or Cornet) we’re all transposing right from the start anyway.

Depending on what your teacher said to you in those very first days you might be aware of that fact, you might not. Let’s assume that you’ve looked at the Types of Trumpet page and read the paragraph on transposition there, and that you’re here because you want to know more about it or perhaps because you’ve been hit in the face with it.

Introduction to Trumpet Transposition

My introduction to transposition came in our city’s youth orchestra. My high school band director had sent me there – probably to bring me down a peg or two (see Trumpet Jokes). I was enjoying playing the loudest instrument in the group at that first rehearsal until things went terribly wrong. I was pretty sure that I was playing great and yet the opening to Meyerbeer’s Coronation March from “The Prophet” sounded all kinds of wrong.

The conductor gave me the hairy eyeball but wasn’t quite sure what to say so he started again. Knowing I was right I played it even louder which had the unexpected result of it sounding even worse. Hmmm. It had never occurred to me that the part could have been printed for a Trumpet in any key other than the one in my hand but sure enough there was a bit of type on the page that read “in Es” – whatever that meant.

The conductor was equally surprised to be faced with a player who had no clue what to do with that instruction and wasn’t really able to explain it. Hilarity did not ensue. We were at an impasse. Thank God for my band teacher.

The Importance of Learning Trumpet Transposition

So – what to do? You have two choices: rewrite the part to match the Trumpet in your hand or learn to play different notes from the ones you’re looking at. The first choice might be the best to get you through an emergency like the one I faced but in the long run it is as limiting as writing in fingerings for a beginning player. It’s not a dead-end street, more of a cul-de-sac. You will be able to play that particular piece in that particular key but it won’t help you with any similar situations in the future (I’m hearing “You Can’t Get There From Here” in my mind’s ear.)

Ideally you should be prepared to play almost anything in almost any key. The truth is much less daunting because there are some pretty standard transpositions that account for most situations so we’ll look at some strategies for those.

Learning Trumpet Transposition Requires Basic Music Theory

If you don’t already have a basic understanding of how key signatures and intervals work this would be a good time to take a break and go learn that stuff. Don’t feel like it’s a punishment, feel like it’s an opportunity to inform your playing with an enhanced depth of theoretical understanding. This is Music Theory that you need to know to play well in any case and certainly to transpose well. I’ll use terms like “minor third”, “D Major” and you’ll need to know what they mean.

Oh yeah, one more thing: Let’s assume that you can play all 12 major scales. Learn them if you haven’t already and while you’re at it memorize them. (Ok, that reminds me of the auto repair manual that says “remove engine” as step one. Sorry if that’s how you feel.)

How to Start Learning Trumpet Transposition

We’re going to start simply with a tune that you’ll recognize. The idea is that you’ll hear any mistakes. Using your ear will be important when the music gets more difficult. Let’s assume that you’re playing on a Bb instrument. The first transposition most of us face is up a step to meet a C instrument part. To do that we play each note one step up and add two sharps to the key signature (or subtract 2 flats (or subtract a flat and add a sharp)). The order of sharps or flats in a key signature is another thing you’ll have memorized by now.

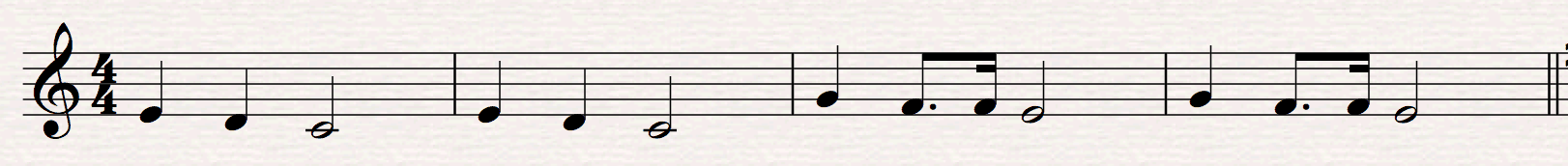

First Exercise:

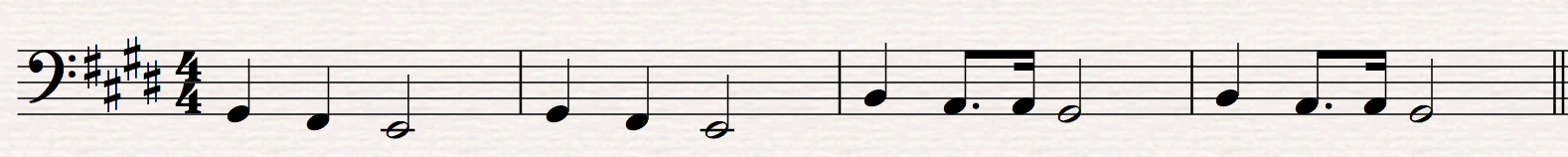

Play this tune as it appears:

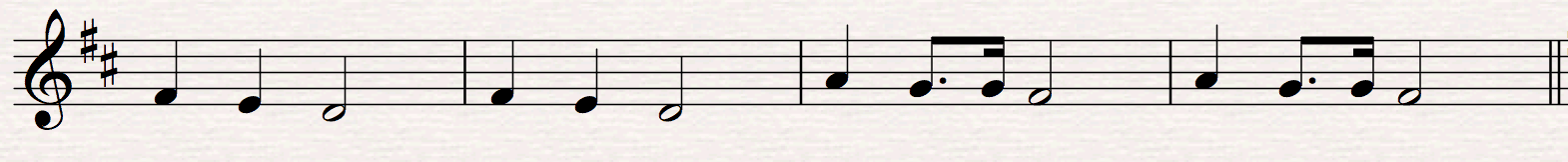

Now play it here (up a step in D):

scroll down

scroll down

scroll down

scroll down until you can’t see the music above

… just a little more

Now play it up a step in D while looking at this – it should sound the same:(Don’t cheat by looking at the example above.)

Trumpet in C

Get your head into D Major rather than counting semitones to get the F#. If it doesn’t sound right you’re missing something. Go back and check if you must.

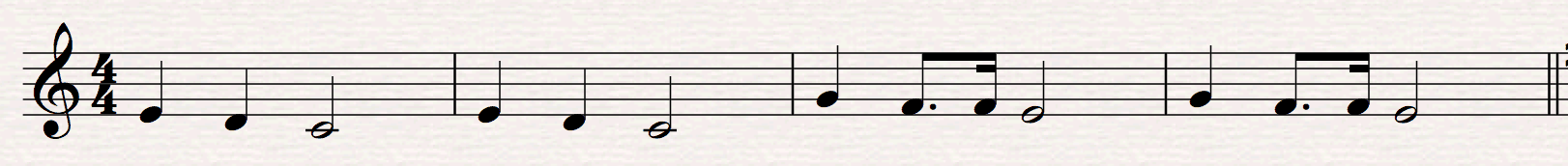

While we’re at it let’s take it up another step as though it’s a Trumpet in D part. You’ll be in E Major (4 sharps) and up two steps (the distance from Bb up to D). If you can convince your brain that the lines are one above where they really are that could work for you. This might be the right time to introduce you to the Bass Clef. If you are a piano player you’re already ahead of me. If the Bass Clef is a mystery to you it’s worth getting to know just for this transposition. The lines in Bass Clef are G B D F A instead of E G B D F so … If you read a part as though it’s printed in Bass Clef and make the correction to the key signature you’ll be playing Trumpet in D on your Bb Trumpet. Make sense? Here’s what it would look like (if you were looking at it, which you’re not). It’s an octave or two below where it sounds, but we’re looking for solutions, not picking nits.

This example is low, but hopefully you can see how it works. Notice that we’re using the key signature, not accidentals. Almost everything we play is tonal, so key signatures help keep things less cluttered and reduce the math we have to do.

While we’re fooling around with Bass Clef I feel the need to tell a Viola joke.

Way back when the internet was only available to universities as a means of accessing each others’ libraries there sprang up an anonymous collection of Viola jokes. If you’re not sure what a Viola is that’s ok, just know that most musician jokes started as Viola jokes. (btw You do know the difference between a Violin and a Viola, right?)

We only care about the Viola because they read their music (again we’re making assumptions) off a completely different clef from everyone else – the Alto Clef. Do a little digging and you’ll find that the Alto Clef is not alone. The Tenor Clef is nearby, lurking and making itself available as well. They occupy the nether regions between Treble and Bass by indicating different clef lines as C. Which is which doesn’t matter to us as much as borrowing their movable quality.

If C can occupy different lines, it can occupy any line. If you combine that with your cat-like ability to transpose up or down a step (not really that hard when you get used to it) you can get almost anywhere. The only downside is that you have to be able to see C as occupying a line instead of a space. If a Viola player can do it …

oh yeah, a viola burns longer.