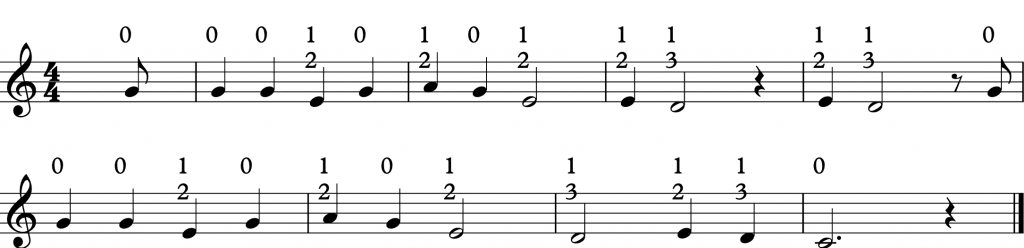

There is a melody below with 24 notes in it. There are 16,777,215 ways to arrange 24 things, and notes can be all over the place. Granted, several are the same note so that cuts things down somewhat but you get the idea. To complicate things, though, there are some notes in the tune that share the same fingering, some notes that have more than one fingering (which they share with other notes) and plenty of notes that use the fingerings of the notes you see but which are way far away. Maybe that 16 million figure wasn’t far off.

Get a helper to scroll down to the SPOILER paragraph so that they know what you’re doing. If you really can’t play it without the fingerings just scroll down to version 2, but I don’t think it’ll fix things the first time through.

Play this tune while somebody listens to you:

Version 2 – with the fingerings (if you insist):

SPOILER/Listener

If you’re the Trumpet player taking the test don’t look at this until you’re done. If you’re the listening helper, read on…

The tune is an old one called the Camptown Races. It goes like this:

The Camptown ladies sing this song; Doo-dah Doo-dah,

The Camptown racetrack’s five miles long; Oh, Doo-dah day

It should sound like this:

Any note you think isn’t absolutely right counts as a mistake. If you run out of fingers and toes give your friend a second chance. Once they recognize the tune it should get better.

How did you do?

This tune is dead easy if you know the 6 notes in it. Those notes are covered by most beginning band classes in the first couple of months, so it should be playable. The test has more to do with getting the right notes out in the presence of nearby wrong notes that might be coming out instead.

E and A share a fingering – either could come out

G shares a fingering with C – likewise

G also shares a fingering with D. It’s rarely used for G on purpose, but that sneaky G pops out all by itself sometimes when you think you’re playing D.

Students who look at the notes usually do better on this test than the ones who look mostly at the fingerings. There are reasons we want to look at the notes. The most important right now is that they show us how high or low a note is – information that the fingering doesn’t have.

If you played the tune perfectly, well done. That was decent reading. If you played 20 or more right notes you’re probably getting the idea and will likely play it perfectly before you leave this post.

If you made a bunch of mistakes then you aren’t yet following the noteheads up and down the page as well as you will be soon. Go back up and try the tune again now that you know what it is and how it sounds. If you’ve been using written-in note names or fingerings they are getting in your way. It’s time to leave them behind so that you can look at a note and know how high or low it it. This melody is easy enough that it can help you do this. Go back up to the first version, the one without fingerings and look at those noteheads as you play. Do the same thing with your favourite lines from your method book or pieces of music. Get the eraser out if you have to. Look at the notes as you play familiar tunes – that will help. I guarantee it or you get a full refund 🙂

Leaving the written-in fingerings behind is a lot like leaving training wheels behind. It might be a little scary but as soon as you get your balance you’ll never even think about going back.